Some advice for scientists in the church

Posted at 10:00 on 03 June 2019

When I wrote my advice for pastors on how to handle science, I made a number of suggestions. I said that they should not be afraid to admit that they don't know what they don't know; that they should seek counsel in scientific matters from professional scientists in the church; and that they should not allow anyone with no scientific training to teach about science in their churches. I also followed up a few months later with some advice for non-scientists in general. But what about scientists in the church?

When I first started discussing creation and evolution on Facebook about three years ago, my plea then -- as it is now -- was for honesty and factual accuracy in the claims that we are making. While this plea was mostly well received by my friends in the church, I did experience some push-back from young-earth creationists, who duly trotted out the usual arguments from Answers in Genesis and their ilk.

This was, of course, only to be expected. But what shocked me the most was the biochemist who told me that he found the argument for a young Earth from population growth to be convincing -- and reminded me that he was a scientist.

Ignorance or dishonesty?

Now I don't expect non-scientists to be able to see the problem with the population growth argument -- or indeed, any other bad argument. They don't have the skills, training and experience to be able to do so. When presented with evidence that contradicts them, they can always excuse themselves by saying that they're not scientists, and it's all too complicated for them.

You and I do not have the luxury of that excuse.

Fellow Christians who are scientists, or who have any form of scientific training, listen to me very carefully here. If you tell me that you are a scientist, you are telling me that you understand the basic rules and principles of how measurement works. You are telling me that you are mathematically literate. You are telling me that you understand error bars, extrapolation, statistics, confidence levels, sample sizes, controls, random errors, systematic errors, signal to noise ratios, the difference between necessary and sufficient conditions, and the like. You are telling me that you have the understanding necessary to fact-check your claims, to consult their original sources and check that they say what they are being made out to say. You are telling me that you have been trained in the kind of rigorous and exact thinking that science demands. You are telling me that you understand what distinguishes a good argument from a bad one.

Anyone with that level of understanding should spot the flaw in the population argument immediately. The Earth's population has not always increased exponentially throughout history. There have been times when it went down as well as up, such as during the Black Death outbreak from 1347 to 1351. The rate of change has increased substantially since the Industrial Revolution as technology and medical care have improved. Furthermore, in pre-agricultural times, it could well have simply fluctuated over the many millennia of hunter-gatherer societies without seeing any long-term growth at all. The extrapolation is simply not valid.

A claim such as this would merely be ignorance if it were made by a non-scientist. But for a scientist to make arguments such as this one, knowing full well that measurement and mathematics do not work like that, is dishonest.

The scientist's responsibility

As a scientist, you will no doubt find that your pastor, or your friends in your church, look to you for guidance on scientific matters from time to time. This being the case, you have an extra responsibility before God to take extra care that your advice is honest and factually accurate.

Now to be fair, some claims (such as the RATE project's research on helium diffusion in zircons) are complex and difficult to fact check. Some may require specialist knowledge or even field research to examine the evidence for yourself. But other claims are blatantly and obviously untrue. Sample sizes may be obviously tiny. Error bars may be obviously huge. Assumptions may be obviously invalid. Claims about the evidence itself may be obviously exaggerated or even outright untrue. Evidence contradicting them may be no more than a Google search away. They may contain obvious misunderstandings or misrepresentations of what scientists actually teach about evolution, or rhetorical questions whose answers are readily available on Wikipedia. (The classic question "what use is half an eye?" -- which was convincingly answered by Darwin himself in On the Origin of Species -- is one such example.)

As a scientist, you have a responsibility to advise your pastor how to avoid such bad arguments. If they end up making ridiculous and easily falsified claims, and losing credibility as a result, you are responsible if you endorsed those claims, or if you advised them that those claims were satisfactory or convincing.

As a scientist, you are a professional. Your professional responsibility does not end when you leave the laboratory and enter the church. On the contrary, within the church, you are in a position of trust, whether you like it or not. Be very careful that you are not abusing that trust.

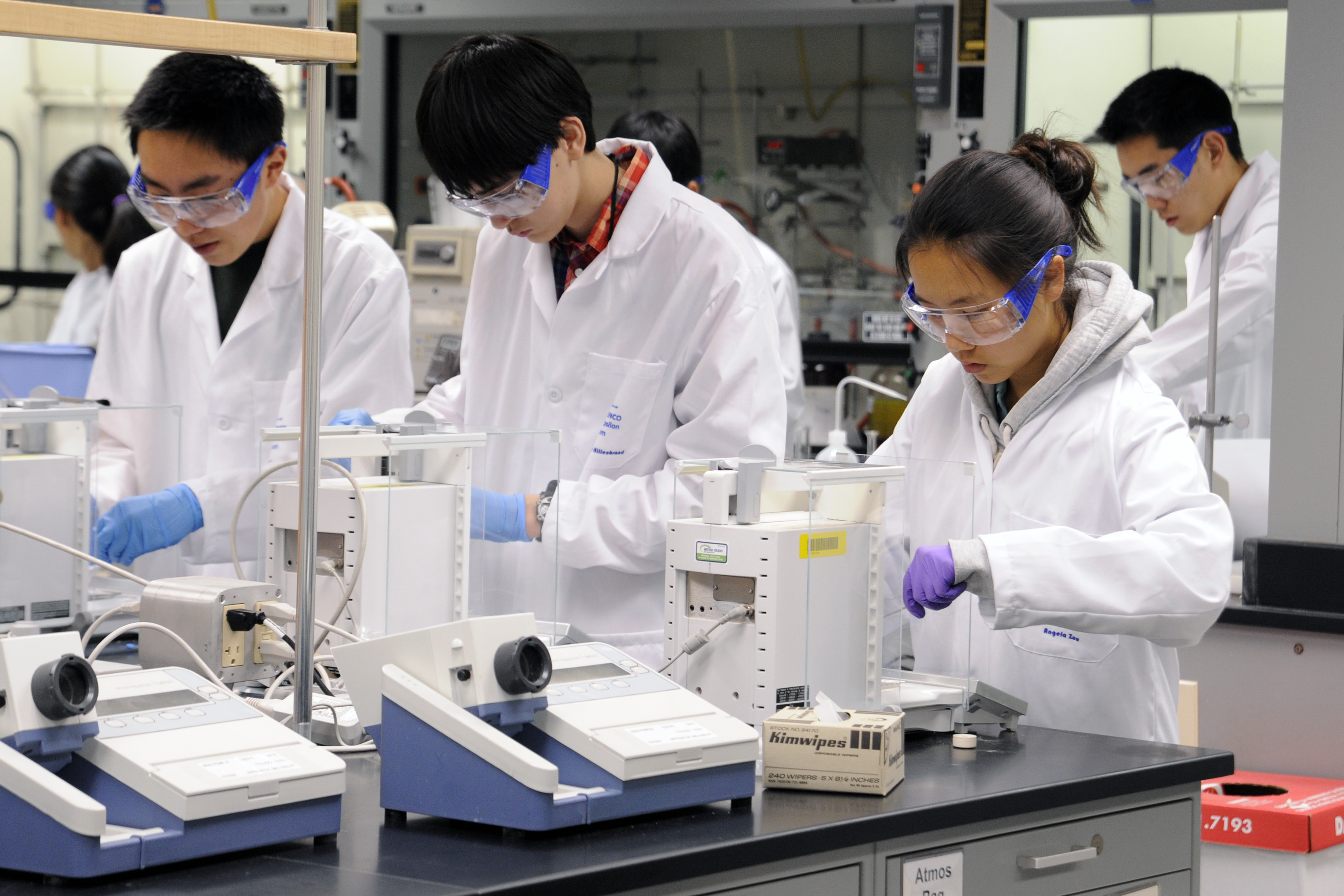

Featured image: United States Air Force Academy