Some advice for pastors on how to handle science

Posted at 10:00 on 27 November 2017

In 2011, Barna Research published the results of a five-year study in which they interviewed a large number of young people to find out their reasons why they no longer attend church. The full results of their findings were published in a book called You Lost Me: Why Young Christians are Leaving Church and Rethinking Church, and a summary of the results was posted in an article on their website titled Six Reasons Young Christians Leave Church.

The third reason that they gave was that many churches come across as antagonistic to science:

One of the reasons young adults feel disconnected from church or from faith is the tension they feel between Christianity and science. The most common of the perceptions in this arena is “Christians are too confident they know all the answers” (35%). Three out of ten young adults with a Christian background feel that “churches are out of step with the scientific world we live in” (29%). Another one-quarter embrace the perception that “Christianity is anti-science” (25%). And nearly the same proportion (23%) said they have “been turned off by the creation-versus-evolution debate.” Furthermore, the research shows that many science-minded young Christians are struggling to find ways of staying faithful to their beliefs and to their professional calling in science-related industries.

For what it's worth, I don't think that the problem is due to any inherent conflict between Christianity itself and science. Rather, it's because most Christians don't know how to respond to science. Most pastors don't know how to advise them either, because they don't have any scientific training themselves. But that's okay: that's not your job. Nevertheless, there are some things you can — and should — do to provide leadership in this respect.

Claims about science demand an informed Christian response.

Like it or lump it, we live in a scientific world. Just about every aspect of our lives is influenced or even controlled by scientific discoveries and research. Many of us work in science-related industries, or have science-related jobs. Furthermore, when matters of public policy are at stake, the first question that policymakers ask is, what does science have to say about the subject? Whether we are talking about stem cell research, or cloning and genetic engineering, or sexuality and gender, or the environment, or abortion, or child discipline, or human origins, or monetary policy, or artificial intelligence, or the Internet, we will have to address claims presented in the name of science.

One of my friends at church is a PhD cell biologist with a special interest in the issue of stem cell research. She has done a lot of work fact-checking the various claims and counter-claims surrounding embryonic stem cell research in particular, and has testified on several occasions before the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee. We need more people in the Church like her.

But such people need to know what they are talking about. They also need to be supported by the rest of the Body of Christ, and consequently we need to make sure that our own approach to science is sensible, honest, informed, and responsible. You cannot expect the world to take you seriously on moral or spiritual issues if you are spouting demonstrable nonsense on empirical, testable matters. Nor can you expect to raise up people to speak on science if they are encountering passive-aggressive, suspicious, or hostile attitudes towards the subject from other people in the church, or if they are being expected to make claims that they know for a fact to be untrue.

There are people who make a business out of lying to Christians about science.

In 1 John 4:1, we read this:

Dear friends, do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, because many false prophets have gone out into the world.

Science is a prime target for professional liars, because many claims are not easy for the layman to fact-check. Some claims are not even easy for professional scientists to fact-check, especially if they are particularly complex or specialised. On the other hand, many scientists are particularly skilled in the art of fact-checking anyway, and so if you encourage suspicion or distrust towards science, or even if you just encourage intellectual laziness in general, you will make your audience all the more vulnerable to people lying about just about anything.

Some people lie about science purely for profit. They know how to make all the right evangelically-correct sounding noises, but they are ultimately motivated by making money, not disciples. Others lie to Christians for sport, to make fools of us and undermine our credibility as effective witnesses for Christ. (The Well to Hell hoax was one notorious example.) And some of them do so for political reasons. It's quite possible, for example, that evangelical climate change scepticism is partially funded, at least indirectly, by the oil industry.

Bad attitudes to science are a very real problem in evangelical circles.

Now the majority of Christians that I know — including many who are sceptical about evolution — have a healthy and responsible attitude towards science. The fact that I live in the UK rather than the USA may help there, if this recent study is anything to go by. But I've encountered enough of the wrong type of attitude to be aware that it is very much a problem.

There are certain people out there who believe that just because they have read a bunch of articles by Answers in Genesis, or watched some creation.com videos, and because they haven't been "brainwashed" by a science degree, that means that they know more about science than "secular scientists."

Yet these are the very people who will quite happily trot out the most staggeringly ignorant falsehoods imaginable. They frequently don't even know young-earth creationism itself very well, let alone the "other side." It's common to hear them repeat arguments that even Answers in Genesis and creation.com tell them to avoid, such as Paluxy River tracks, moon dust, or NASA computers finding the "long day" of Joshua chapter 10.

When it comes to attempting to refute what real scientists actually do and teach, they don't even do the most basic fact-checking. They often aren't aware that radiometric dating actually involves measuring things, and they will happily tell you that Sir Arthur Keith wrote something about evolution being unproven and unprovable four years after he died. One of them told me that DNA is "just carbon," while another of them tried to convince me that the scientific community takes a laissez-faire attitude to fraud — by referring me to an article in The Guardian about a scientist being sent to prison for fraud. It's hard to get more clueless than that.

They are completely unable to answer even the most basic objections in a meaningful way. Their stock answer is usually "It's just an assumption" or "It's just an interpretation" — a response that not only doesn't answer your question, but is very often simply not true. Yet if you point any of this out to them, they respond by accusing you of "compromise," or "trusting man's fallible wisdom instead of God's infallible Word," or even "speaking with the voice of the serpent." I’ve even on one occasion had one such person tell me that I had a “spirit of science” that was “making it difficult for me to hear God.”

It is attitudes such as these that people are thinking of when they talk about Christianity as being antagonistic to science. But sometimes these attitudes get expressed in more passive-aggressive ways. Snide remarks about "secular science" or "putting your faith in science" are one example. Another example is using the terms "evolution" and "evolutionist" interchangeably with "atheism" and as a derogatory umbrella term for everything about science that you don't agree with, even if it has nothing to do with biological evolution whatsoever.

These attitudes are driving away both unbelievers and Christians alike. Do not allow them to undermine your ministry.

Don't be afraid to admit that you don't know what you don't know.

The biggest problem that the Barna survey highlighted in respect to science was that respondents felt that "Christians are too confident they know all the answers."

Of course, when you're out in evangelism, or witnessing to colleagues at work, you'll be asked questions that put you under pressure. When your work colleagues are asking you, "Where did Cain get his wife?" you'll be anxious to come up with something. But the correct answer to this question — and the one that your non-Christian friends and colleagues will respect you the most for — is, quite simply, "I don't know." The Bible doesn't tell us, so any answer we come up with will be wild speculation at best.

It's the same with other questions related to the creation and evolution debate. If you haven't had any formal training in the subject, the best answer you can give is to tell them you don't know because you're not a scientist, and refer them to the BioLogos forums.

If there's one thing about creation and evolution that you need to teach your people more than anything else, it is this: there is no shame in admitting that you don't know what you don't know. Remember that honesty is sometimes the best evangelistic strategy. Trying to convince people that you know what you're talking about when it's quite obvious that you don't will just sound dishonest. Remember too that our faith is about the completed work of Christ on the Cross, and not about the incomplete work of Adam and Eve on their pet dinosaur.

Seek counsel from the trained scientists in your church.

Scientists are trained in critical thinking. Some Christians view critical thinking, reason, or "scientific scepticism" as the antithesis of faith, but it needn't be. On the contrary, it should be seen as a line of defence in your battle against deception, to help you flush out liars who might want to take advantage of you, undermine you, or make a fool of you.

For this reason, you need to take the scientists in your church seriously. If a scientifically trained church member expresses concerns to you about what is being taught in your church about science, try to find out what the problem is. If you have no scientific training yourself, get them together with other trained scientists in the church to either allay their concerns or to propose a recommendation on how to respond. That way, every matter can be established on the testimony of two or three witnesses. But don't just ignore them: they could be crying for help, or warning you that you are walking into a trap.

The Stem Cell Monk blogger suggests appointing a science officer in your church — or, better, a science council. This is an idea that you should perhaps seriously consider. Just make sure the people you appoint are properly qualified.

Do not allow anyone with no scientific training to teach about science in your church.

Not many of you should become teachers, my fellow believers, because you know that we who teach will be judged more strictly.

Anyone that you allow to teach in your church is being placed in a position of trust. In particular, it is a position of trust certifying that they know what they are talking about, that their facts are straight, and that their sources of information are accurate. As a teacher, not getting your facts straight about a subject which you are teaching is a serious breach of trust, especially if it is about something you claim to be important.

I am constantly coming across people telling me that they have lost their faith because they discovered that what had been taught to them by their pastors, their youth leaders, or their Sunday school teachers about evolution and the age of the earth was simply not true. Christian academics in the sciences whom I have spoken to report that time and time again they are confronted with undergraduates coming to them in floods of tears, all of them with the same question: "what else have they been lying to me about?"

This is why I keep saying, over and over again, that you need to make sure your facts are straight. If you believe you must reject evolution, you need to make sure that you are rejecting what scientists actually teach about it in reality, and not a garbled cartoon caricature of it. On the other hand, if you are claiming to have the support of science, you must make sure that the support you claim follows the rules of science.

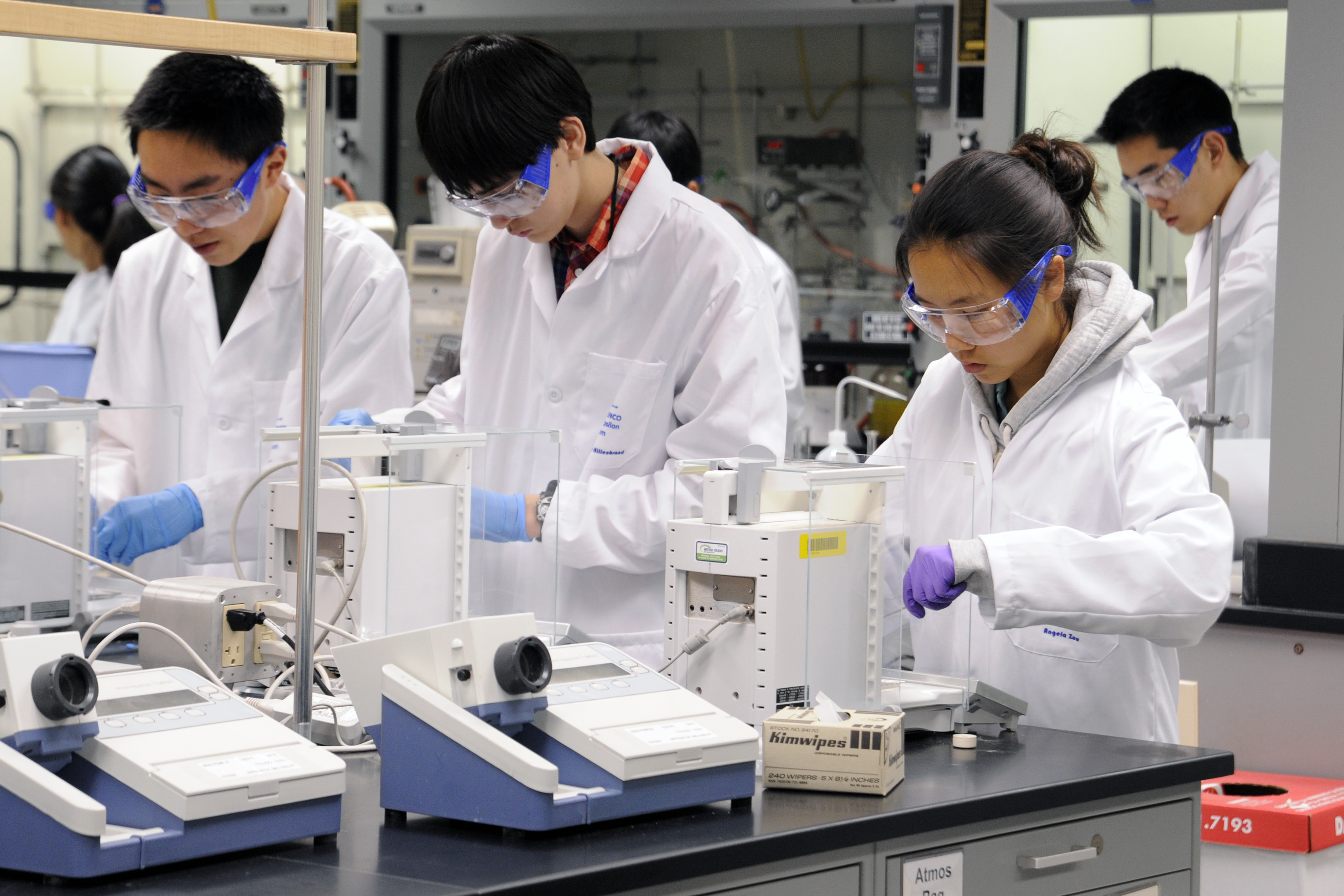

There is much more to teaching science-based apologetics than spoon-feeding your group with creation.com videos. Such an approach may build faith in church on a Sunday, but when they take it into the office, the lab, the classroom or the marketplace on a Monday, it will be tested. You need to be able to teach people to answer objections and to avoid bad arguments. You can't do that if you believe that DNA is "just carbon," or that radiometric dating is "guessing at best." You can only do that if you fully understand how science works, and for that you need to be able to handle the maths, be trained in laboratory procedure, learn how to think in the rigorous, exact, disciplined manner that science demands, and understand the strict standards of quality control that scientific research is expected to meet.

For that reason, if anyone believes that God is calling them to teach in your church about creation and evolution, or any other science subject — whether from the pulpit, or in a small group, or in Sunday school — you should require them to be qualified to do so.

That means a university degree in a relevant Natural Sciences subject at least. Specifically: physics, biology, geology or astronomy.

They should either have one or be willing to get one. If they have any concerns about "brainwashing," ask them why they don't trust God to protect them in it. And if they still aren't willing to start by getting a degree, you should seriously question whether their calling is genuine in the first place.