Just how clean is Uncle Bob's Clean Architecture?

Posted at 09:00 on 17 September 2018

A colleague asked me the other day what I thought about "Uncle Bob" Robert C Martin's Clean Architecture.

It's admittedly not something to which I've given much thought. I've always had a lot of respect for Uncle Bob and his crusade for greater standards of professionalism and craftsmanship in software development. I have two of his books -- Clean Code and The Clean Coder -- and I heartily recommend them to software professionals everywhere.

But I hadn't given much thought to what he says about architecture in particular, so I thought I'd check it out.

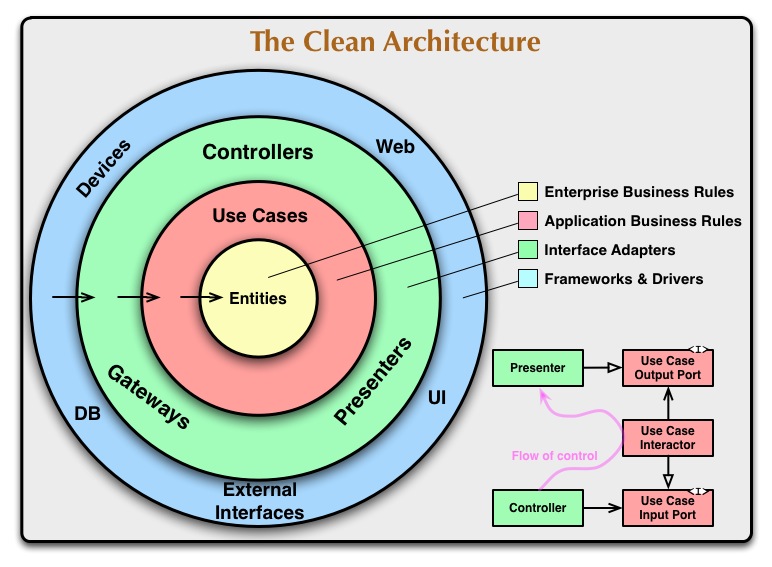

He has written a whole book about the subject. I haven't read it in its entirety yet, but he also wrote a short summary in a blog post back in 2012. He illustrates it with this diagram:

It's basically a different way of layering your application -- one that rethinks what goes where. That's fair enough. One of the things that a clean architecture needs to deliver is clear, unambiguous guidelines about what exactly goes where. A lot of confusion in many codebases arises from a lack of clarity on this one.

But the other thing that a clean architecture needs to deliver is a clearout of clutter and unnecessary complexity. It should not encourage us to build superfluous anaemic layers into our projects, nor to wrap complex, unreliable and time-wasting abstractions around things that do not need to be abstracted. My question is, how well does Uncle Bob's Clean Architecture address this requirement?

Separation of concerns or speculative generality?

Uncle Bob points out that the objective at stake is separation of concerns:

Though these architectures all vary somewhat in their details, they are very similar. They all have the same objective, which is the separation of concerns. They all achieve this separation by dividing the software into layers. Each has at least one layer for business rules, and another for interfaces.

Now separation of concerns is important. Nobody likes working with spaghetti code that tangles up C#, HTML, JavaScript, CSS, SQL injection bugs, and DNA sequencing in a single thousand-line function. I'm not advocating that by any means.

But it's important to remember that separation of concerns is a means to an end and not an end in itself. Separation of concerns is only a useful practice when it addresses requirements that we are actually facing in reality. Making your code easy to read and follow is one such requirement. Making it testable is another. When separation of concerns becomes detached from meeting actual business requirements and becomes self-serving, it degenerates into speculative generality. And here be dragons.

The classic example of speculative generality is the idea that you "might" want to swap out your database -- or any other complex and fundamental part of your system -- for some other unknown mystery alternative. This line of thinking is very, very common in enterprise software development and it has done immense damage to almost every codebase I've ever worked on. Time and time again I've encountered multiple sets of identical models, one for the Entity Framework queries, one for the (frequently anaemic) business layer, and one for the controllers, mapped one onto another in a grotesque violation of DRY that serves no purpose whatsoever but has only got in the way, made things hard, and crucified performance. Furthermore, this requirement is seldom needed, and on the rare occasions when it is, it turns out that the abstractions built to facilitate it were ineffective, insufficient, and incorrect. All abstractions are leaky, and no abstractions are more leaky than ones built against a single implementation.

You really don't want to be subjecting your codebase to that kind of clutter. It is the complete antithesis of every reasonable concept of "clean" imaginable. In any case, if it's not a requirement that your clients are actually asking for, and are willing to pay extra for, it is stealing from the business. It is no different from taking your car to the garage with nothing more than faulty spark plugs and being told you need a completely new engine.

Ground Control to Uncle Bob

So how does Uncle Bob's Clean Architecture stack up in this respect? It becomes fairly clear when he lists its benefits.

1. Independent of Frameworks. The architecture does not depend on the existence of some library of feature laden software. This allows you to use such frameworks as tools, rather than having to cram your system into their limited constraints.

2. Testable. The business rules can be tested without the UI, Database, Web Server, or any other external element.

3. Independent of UI. The UI can change easily, without changing the rest of the system. A Web UI could be replaced with a console UI, for example, without changing the business rules.

4. Independent of Database. You can swap out Oracle or SQL Server, for Mongo, BigTable, CouchDB, or something else. Your business rules are not bound to the database.

5. Independent of any external agency. In fact your business rules simply don’t know anything at all about the outside world.

Points two and three are good ones. These are points that true separation of concerns really does need to address. We need to be able to test our software, and if we can test our business rules independently of the database, so much the better -- though it should be borne in mind that this isn't always possible. Similarly, just about every application needs to support multiple front ends these days: a web-based UI, a console application, a public API, and a smattering of mobile apps.

But points 1, 4 and 5 are the exact problem that I'm talking about here. They refer to complex, fundamental, deeply ingrained parts of your system, and the idea that you might want to replace them is nothing more than speculation.

Point 1 actually makes two mutually contradictory statements. A "library of feature laden software" is the exact polar opposite of "having to cram your system into their limited constraints." In fact, if anything is "cramming your system into their limited constraints," it is attempting to reduce your system to support the lowest common denominator between all the different frameworks.

When I get to point 5, I have to throw my hands up in the air and ask, what on earth is he even talking about here?! Business rules are, by their very definition, all about the outside world! Or is he trying to tell us that we need to abstract away tax codes, logistics, Brexit, and even the laws of physics themselves?

When I read things like this, it reminds me of one thing. This essay by Joel Spolsky:

When great thinkers think about problems, they start to see patterns. They look at the problem of people sending each other word-processor files, and then they look at the problem of people sending each other spreadsheets, and they realize that there’s a general pattern: sending files. That’s one level of abstraction already. Then they go up one more level: people send files, but web browsers also “send” requests for web pages. And when you think about it, calling a method on an object is like sending a message to an object! It’s the same thing again! Those are all sending operations, so our clever thinker invents a new, higher, broader abstraction called messaging, but now it’s getting really vague and nobody really knows what they’re talking about any more. Blah.

When you go too far up, abstraction-wise, you run out of oxygen. Sometimes smart thinkers just don’t know when to stop, and they create these absurd, all-encompassing, high-level pictures of the universe that are all good and fine, but don’t actually mean anything at all.

These are the people I call Architecture Astronauts...

I'm sorry, but if making your business logic independent of the outside world isn't architecture astronaut territory, then I don't know what is.

Clean means less clutter, not more

There are other problems too. At the start, he says this:

Each has at least one layer for business rules, and another for interfaces.

This will just encourage people to implement Interface/Implementation Pairs in the worst possible way: with your interfaces in one assembly and their sole implementations in another. While there may be valid reasons to do this (in particular, if you are designing some kind of plugin architecture), it shouldn't be the norm. Besides making you jump around all over the place in your solution, it makes it hard to use the convention-based registration features provided by many IOC containers.

Then later on he speaks about what data should cross the boundaries between the layers. Here, he says this:

Typically the data that crosses the boundaries is simple data structures. You can use basic structs or simple Data Transfer objects if you like. Or the data can simply be arguments in function calls. Or you can pack it into a hashmap, or construct it into an object. The important thing is that isolated, simple, data structures are passed across the boundaries. We don’t want to cheat and pass Entities or Database rows. We don’t want the data structures to have any kind of dependency that violates The Dependency Rule.

This is horrible, horrible advice. It leads to the practice of having multiple sets of identical models for no reason whatsoever clogging up your code. Don't do that. It's far simpler to just pass your Entity Framework entities straight up to your controllers, and only transform things there if you have specific reasons to do so, such as security or a mismatch between what's in the database and what needs to be displayed to the user. This does not affect testability because they are POCOs already. Don't over-complicate things.

Of course, there may be things that I haven't understood here. As I said, I haven't read the book, only the blog post, and he no doubt mentions all sorts of caveats and nuances that need to be taken into account. But as they say, first impressions count, and when your first impressions include a sales pitch for layers of abstraction that experience tells me are unnecessary, over-complicated, and even outright absurd, it doesn't exactly encourage me to read any further. One of the things that a clean architecture needs to deliver is the elimination of unnecessary and unwieldy layers of abstraction, and I'm not confident that that is what I'll find.